Baby (Ansel Elgort), the boy wonder driver who has been jacking cars since he could see over the dashboard, gets mixed up with a bad gang when he accidentally grabs a load of "merchandise" along with a car. To get square with Kevin Spacey's mob boss Doc, he's forced to be the getaway driver for every heist Doc sets up until his debt's paid off. Balancing the criminal side of his life with taking care of his elderly guardian and making time for his newfound love down at the diner (Lily James, whose look echoes Shelly from Twin Peaks right down to the hairstyle) is the guiding force of the film, weaved together by a pretty serious and uninteresting backstory for Baby (a car crash early in his life took his parents and most of his hearing) whose best result is allowing for the neat musical moments Wright sprinkles throughout the chases and more light-hearted scenes. If you go back to his initial version of the film’s idea in a music video he made with the Spaced cast and imagine the music extending into the ensuing escape, you should get a good idea of the film at its most enjoyable, when the tires are screeching and the gears are shifting in step with the score. Even these high points, though, still feel undercut by the superficial natures of the people in the car.

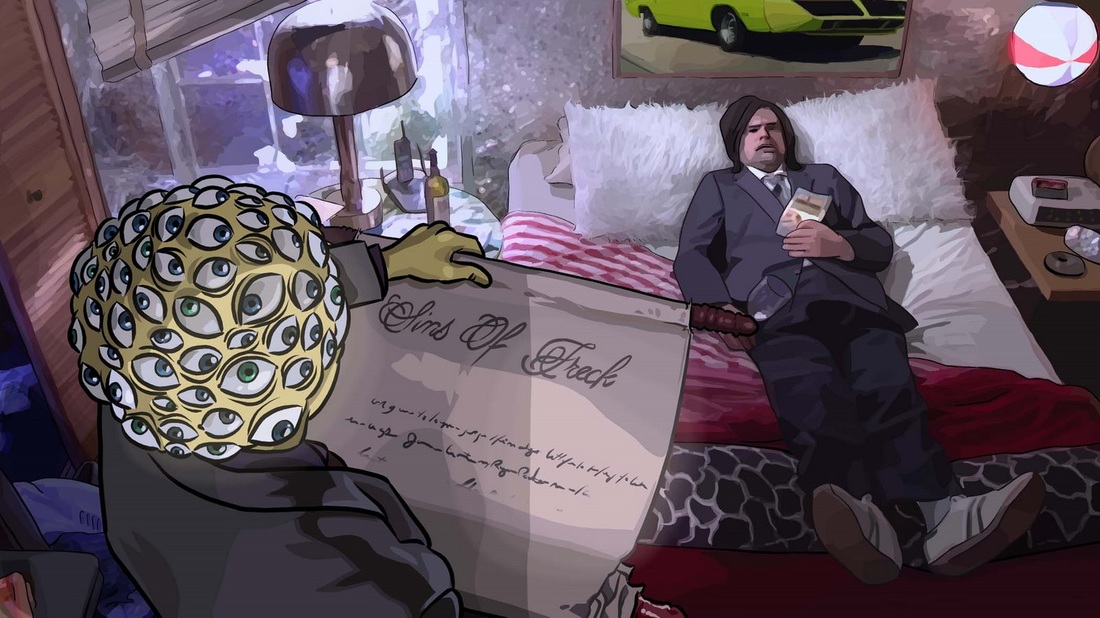

The key to the film’s appeal is it’s simplicity, and the scene of Baby sampling a conversation between two brutal criminals for an electronic track is a glimpse of how Wright might have extended the setup’s innocent charm to the rest of the story, but his decision to lead the characters down a more serious and complicated path leaves the premise and it’s execution at odds with each other. The idea definitely works for the music video format: we don’t have time to know who any of the robbers are or what their plan is, so we just get to see the getaway driver bop along to some music. For the film version, Wright took the opposite approach to April’s Free Fire, where the idea of a gun deal gone wrong would have been enjoyable in a 10 minute YouTube video but was stretched over an hour and a half, by scattering short, great scenes across a story that merely ties them together.

Grade: B-

RSS Feed

RSS Feed