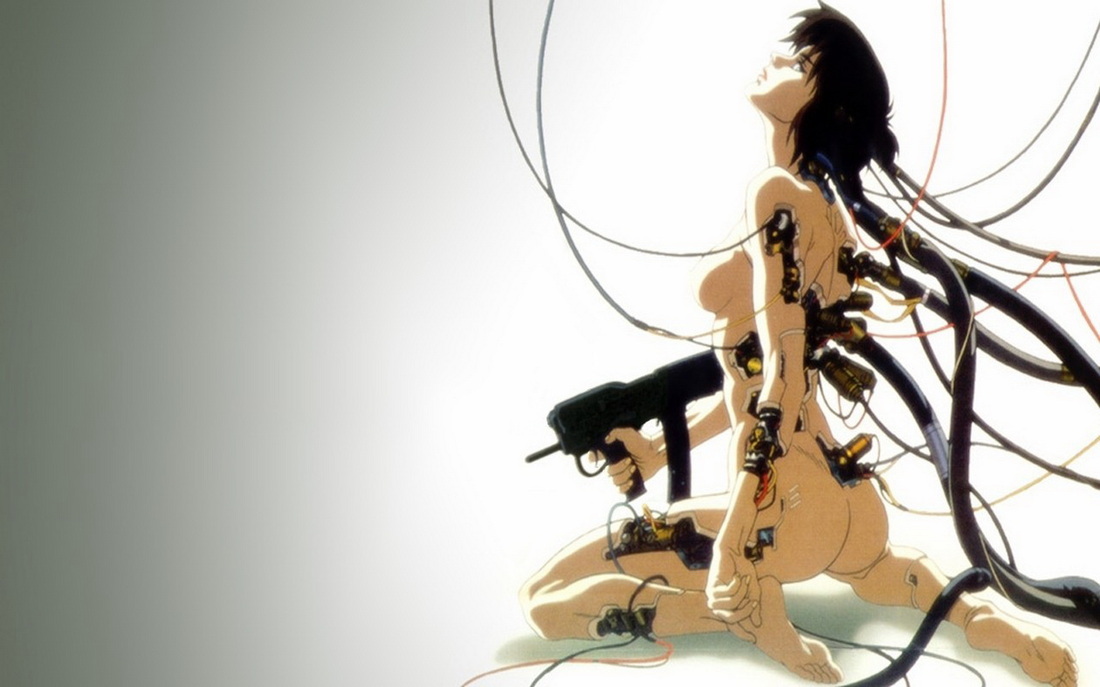

-Motoko Kusanagi

Genre: Cyberpunk

Creators: Masamune Shirow and Mamoru Oshii

Studio: Production I.G.

Length: 82 minutes

Year: 1995

Highlights: The anime equivalent of Bladerunner and The Matrix

In order to combat these threats, the Japanese government created a special security force specializing in cyber-terrorism called Section 9. The leader of the team is Motoko Kusanagi, a cyborg with almost none of her original body left. She works alongside her partner, Batou; tech-specialist, Ishikawa; and new member, Togusa. After a string of brain-hackings of government officials, Section 9 is assigned the Puppet Master case. As they delve deeper into the mystery of the Puppet Master, they begin to discover a government conspiracy and to question the nature of their own reality.

Ghost in the Shell, based off the manga series by Masamune Shirow, is a seminal work of both anime and science fiction as a whole. I often describe it as the anime equivalent of Ridley Scott’s Bladerunner. It is heavily influenced by both the visual aspects of that film and the tone. Visually, the film is dark, moody, and full of decayed cityscapes. It is almost always raining, and when it’s not raining the sky is always gray. In terms of tone, the movie is divided between long scenes of philosophical pondering and intense scenes of action, often with quite graphic results (although most characters are cyborgs, so the gore is of a much more mechanical variety).

As I mentioned before, it is quite common for people in the Ghost in the Shell universe to have all or most of their body replaced with machines. Therefore, it is only natural for those people to wonder exactly how human they really are. A major theme in the film is how people construct their own reality and identities and how those identities begin to break down when exposed to too much doubt. Many writers have also commented on the film’s portrayal of sexual and gender identity in a transhuman setting, commenting on the juxtaposition of human sexuality with cold and precise machinery. Ironically, the manga had a much lighter tone, and sometimes played these themes for laughs rather than drama. The film’s more sombre and serious tone is nearly universally considered superior.

These themes of questioning, doubt, and identity, while inherited from older cyberpunk movies like Bladerunner, would in turn go on to inspire a new generation of filmmakers. The Wachowskis, after viewing Ghost in the Shell, decided that, "We wanna do that for real.” The result was, of course, The Matrix. Ghost in the Shell was also a major influence on Western perceptions of anime for many years, showing an American audience that animation could be mature, intellectual, and exciting. The mid 1990s were a time when most Americans were unaware of anime, and associated animation almost invariably with Disney (for comparison, the most recently released Disney films were Pocahontas and The Hunchback of Notre Dam). In the end, while popular in Japan, Ghost in the Shell is generally much more well-received by Western audiences and is considered a seminal classic by that audience.

Although science fiction is often associated with space battles, bizarre aliens, and people in tight spandex suits, the best of the genre can act as a mirror for the people who create and watch it. It lets us examine ourselves in a way that is only possible when our base assumptions about ourselves, society, and the universe are questioned. This is why we remember such films as Bladerunner, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Solaris and The Matrix as classics of the genre. Along with those classics stands Ghost in the Shell, because the only times we can truly know who we are is when our existence is questioned.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed